by Linda Charlton

“The visit from La Grippe is over.” So read the November 7, 1918 edition of the Clermont Clarion. The headline wasn’t entirely true as La Grippe, better known as the Spanish* flu, did linger a bit; however, the date highlights a major difference between the influenza pandemic of 100 years ago and the covid-19 pandemic of today. The deadly variant of the Spanish flu hit different parts of the world at different times, spread over a three-year period (1918-20), but when it did hit it was typically gone within about three months. In places where the Spanish flu returned, it once more came and went quickly. And in an apparent nod to ‘herd immunity,’ the subsequent wave of flu was in most cases milder. The only known exceptions were areas in this country (and maybe a few troop disembarkation points across the Atlantic) that experienced the relatively mild version that hit in the spring of 1918, followed by the deadly version that hit five months later.

The deadly version of the Spanish flu first hit the United States in August 1918, on ships coming from the war in Europe. It peaked in this country in October, with 100,000 deaths in that month alone. Lake County was off the beaten path, and did not record its first pandemic death until October. There were seven (7) deaths in October, nine (9) in November and four (4) in December. The equivalent with today’s population would be about 600 deaths — a figure which it took the county about a year to reach during this covid-19 pandemic.

While the covid-19 toll is still rising, the toll world-wide from Spanish flu is generally put at 50 – 100 million. With the lower figure, that means an average of 1 person in 150 dying of Spanish flu, versus 1 in 500 dying of covid-19. In 1918 Lake County, with a population of around 12,000, the Spanish flu death rate works out to 1 person in 600. All in all, it was a good place to ride out that earlier pandemic — unless, maybe, you were in one of the lumber camps deep in the south end of the county, in an area locals sometimes referred to as no-man’s land.

Julian Rowe (1915-2015) and Harry Judy (1914-2012) were both born and raised in south Lake. Both were well aware that in the peak lumber days, Groveland was the economic powerhouse of Lake County, boasting the largest lumber mill in the southeast. And Judy knew first hand that in the those days, because of the lumber camps, there were more black people than white people in the south end of the county. The men and families in the camps worked together, ate together, and slept together, single men in barracks, families in cabins. One of the statistical oddities of the Spanish flu in the United States was that black communities, in general, were not hit as hard as white communities. That didn’t happen in Lake County. Of the 20 Spanish flu deaths recorded in the county, 13 of the dead were persons of black African descent. There’s no way of knowing whether the crowded conditions in the lumber camps lead to a deadly outbreak, but it is plausible. If so, those victims are most likely buried in the abandoned Pine Camp Cemetery, located deep in the middle of nowhere.

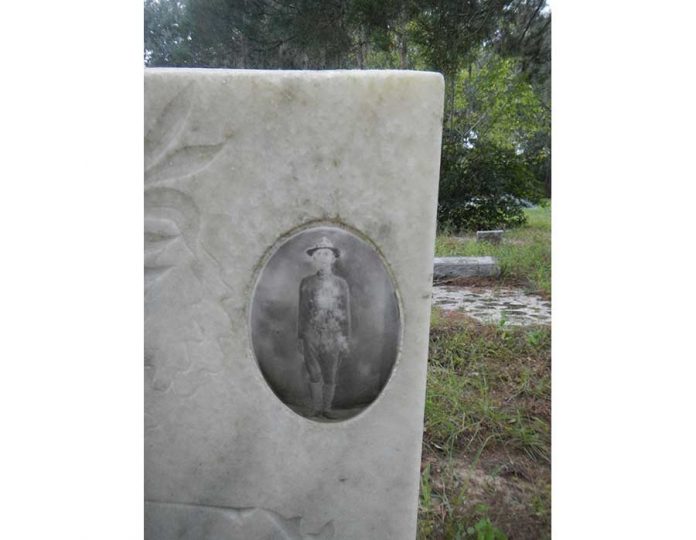

In addition to the deaths locally, three of the local residents serving out of state in the military died of the Spanish flu. All three were from south Lake. Eugene Bryant, a private in the marines, died in Brest, France — where many researchers believe the deadly “second wave” variant of the Spanish flu first took hold. The American Legion post in Clermont was named in his honor. Bret Hart, a seaman, died in hospital in Rhode Island and is buried in Mascotte. Thomas William Grover, an army recruit, died in hospital in Georgia and is buried in Dukes Cemetery in Groveland. His image is on his tombstone and is arguably the only image of the homegrown Spanish flu victims to survive.

Supply chains were not an issue.

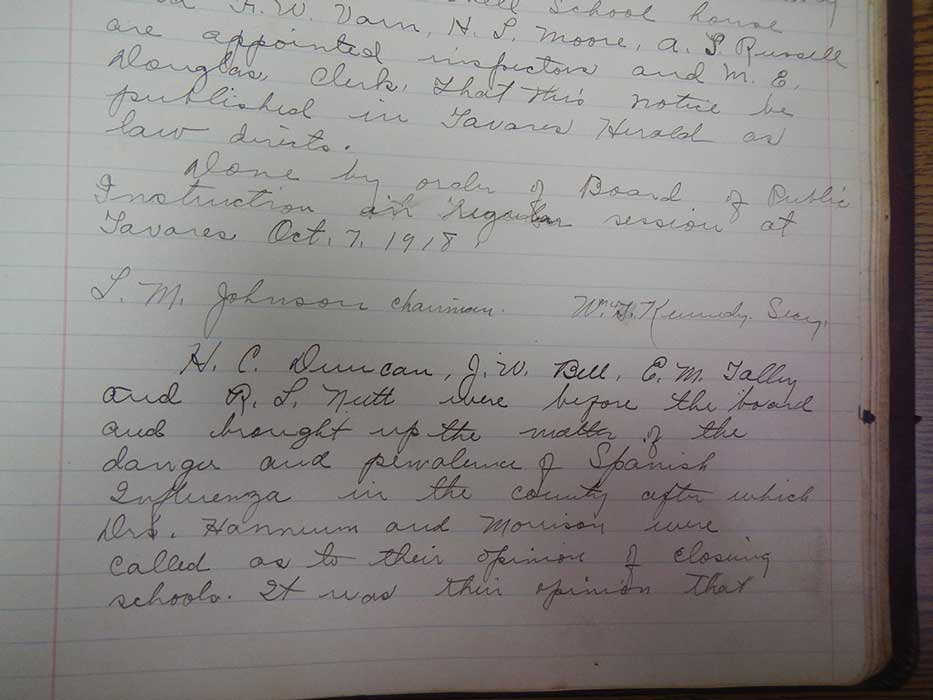

Schools closed, but not for very long.

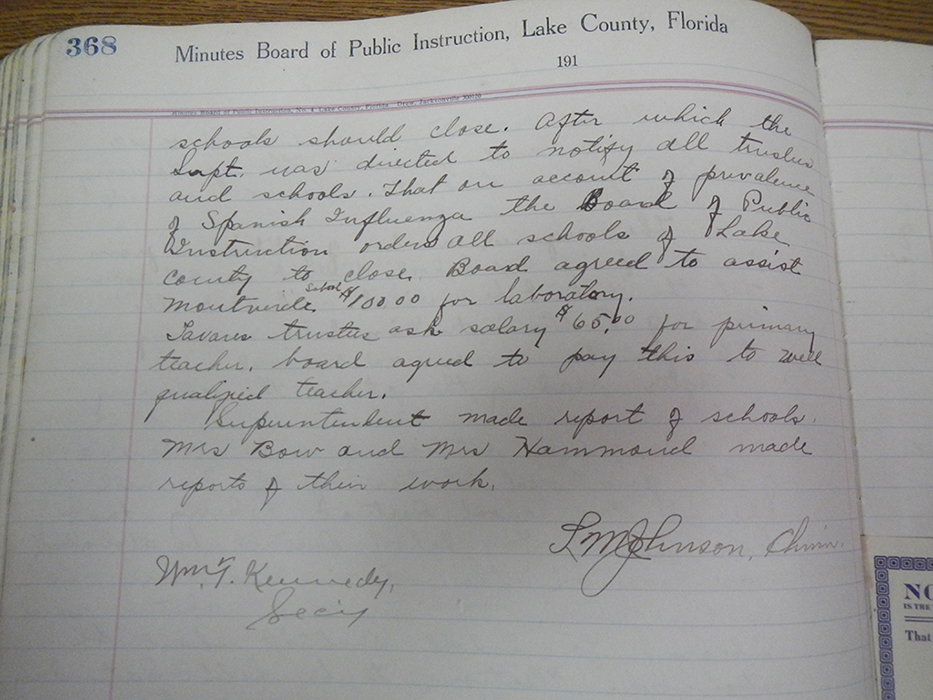

During the October 7, 1918 meeting of the Board of Public Instruction in Tavares, the question of whether to close the schools came up. Two doctors in the audience were consulted, and the school board secretary dutifully recorded that “It was their opinion that the schools should close. After which the superintendent was directed to notify all trustees and schools that on account of prevalence of Spanish Influenza the Board of Pubic Instruction orders all schools of Lake County to close.”

Dates of re-opening were left to the trustees of individual schools, who were directed to consult with city officials, as appropriate. Two weeks later the board approved that the now out-of-work teachers would be paid a subsistence wage for their time off: $20 per month for most of the county, $32 for Clermont and $10 for teachers in two “Negro” schools. The payment was authorized for a maximum of one month. By coincidence (or not) the trustee of the Clermont-Minneola School, together with the Clermont mayor, officially reopened the Clermont-Minneola School just one month after it closed.

The proclamation, dated Nov. 6, 1918, reads that “On and after this date we deem it advisable to allow churches, schools, theaters and public gatherings to resume their natural functions.”

There’s nothing in the Clarion or in Clermont council minutes or Board of County Commissioners minutes about closing or limiting public gatherings. There’s not even anything there about the school closure. Apparently, there were no mandates in the south end of the county (aside from the schools closing). Churches and theaters and organizers of public gatherings thought for themselves, and did what they thought best.

As for the disease itself, the best advice from U.S. surgeon general Rupert Blue seems to have been don’t get it and don’t spread it. Blue advocated fresh air and urged caregivers and others to not directly breathe in the air that a sick person has breathed out. Masks or folds of gauze were recommended. A recurring slogan of the era was “Coughs and sneezes spread diseases as dangerous as poison gas shells.”

Writing of the Spanish flu in an October 1918 U.S. Health Service bulletin, Blue says “It is important that the body be kept strong and able to fight off disease germs. This can be done by having a proper portion of work, play and rest, by keeping the body well clothed, and by eating sufficient wholesome and properly selected food … In most of the cases the symptoms disappear after three or four days, the patient then rapidly recovering. Some of the patients, however, develop pneumonia, or inflammation of the ear, or meningitis, and many of these complicated cases die.”

By December the messaging from Blue had changed. In what was basically a post-Spanish flu society, he warned people to be “vigilant about the other respiratory ailments.” He also urged people to “be a fresh air crank.”

*Back in that October Health Bulletin, Blue also made clear that there is nothing “Spanish” about the Spanish flu. Without mentioning that there is a case for the Spanish flu to have started in or near a Kansas army base, Blue discusses what the Germans were saying: that there was a major outbreak of influenza in China (the Eastern Front) in the summer and fall of 1917. As several writers have reported, Chinese support personnel for the war effort made their way across Canada in early 1918, not long before that first case of Spanish flu was recorded n Kansas. The French reportedly blamed the start of their deadly wave of Spanish flu on soldiers returning from Switzerland, where they would have been exposed to sickness was afflicting the Germans held there.

The when or where the Spanish flu shifted from bad epidemic to deadly pandemic may never be determined, but scientists have figured out the ‘how.’ The virus that caused it was an H1N1, a bird flu. The “H” is the influenza equivalent of the covid-19 spike protein. It determines how the virus attaches to the host. The military hospitals during WWl were very good about taking tissue samples of soldiers and seaman who contracted the flu. Many of those samples have been sequenced. As reported in Pale Rider (Laura Spinney’s best selling book on the Spanish flu), one-quarter of the samples from the spring wave of flu had Hs that were best adapted to humans, three quarters had Hs best adapted to birds. By the fall, those figures were reversed. The virus was then way more transmissible, it would have spread within the body more rapidly, and the chances of the patient having a deadly ‘cytokine storm’ reaction goes up. Indeed, Spinney reports that while the numbers of flu patients dropped off for several months after the spring 1918 wave, the percentage of patients who died from it went up.